Closing the hybrid working gap

William Dougherty

Oct 24

Lawyers want to spend more time working from home than their firms are comfortable with. This is the hybrid working gap, the crux of the ongoing debate about the future of work. Here, we look at how firms might close that gap – not by forcing people into the office, but by making the office a place they are more enthusiastic to attend.

We’ve been watching law’s hybrid working debate with interest – not because we have a horse in the race, but because we think that some firms are going to emerge from this period of change with exactly the right formula to attract and retain skilled and motivated lawyers.

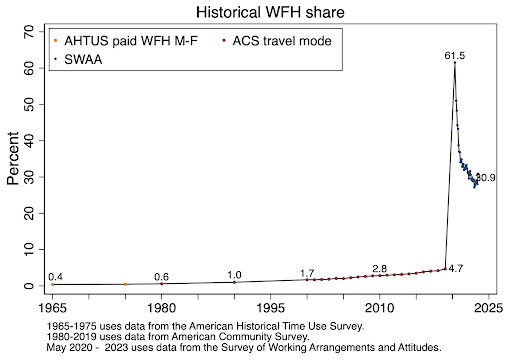

And it has been huge and sudden change, as this graph from WFH Research illustrates:

Remote working didn’t happen gradually but in one great leap. It should surprise no one that firms have yet to land on the optimal approach to its successor, hybrid working. But we do know that employers are listening to, and compromising with, the desires of their workers. Here’s data gathered from US workplaces, with “days working from home” on the y-axis.

That’s progress. But so long as there remains a gap between the lines on that chart, hybrid working will remain contentious – driving talent away, contributing to employee disengagement, and even inflaming generational tensions in law offices. Put another way, the hybrid working sweet spot is at the intersection of those lines, where no gap exists between a firm’s hybrid approach and the policy its lawyers desire.

Mind the gap

So how might firms close the hybrid working gap? The simplest way is for firms to meet the demands of their workers directly. Yet firms have good, solid reasons not to. You’ve heard all the arguments before, about cultural cohesion, collaboration, relationship building, and skills development. We think the majority of workers know, deep down, that these are valid arguments.

The other option is for firms to encourage workers to revise down the number of days they wish to work from home. That means winning hearts and minds, not mandating attendance. Mandates, or other policies that favour the stick over the carrot, succeed in drawing lawyers into the office, but against their will. A hearts and minds approach, on the other hand, closes the hybrid working gap by making workers actually want to spend more time in the office.

Of course, some lawyers want that anyway. Our Lawyers in Focus report found that some lawyers feel their jobs would be improved by more in-person interaction, especially opportunities to socialise face-to-face. Others feel more productive in the office, while some recognise the career benefits of working in the same room as seniors.

But we must remember that hybrid working desires are often personal. For every lawyer who gladly makes the 20-minute commute because noisy flatmates are at home, there’s another who lives an hour from the office and shoulders the family’s childcare responsibilities. As you might expect, these different motivations are associated with gender and socioeconomic background, making hybrid policymaking all the more delicate and at risk of unintended discrimination.

Here’s the good news: there are some simple incentives, informed by research, that can help close the hybrid working gap. We’ve identified three from the many hybrid working studies we’ve read over the past three years.

1. It might be the journey, not the destination

Because we often talk about the benefits of hybrid working in nebulous terms like “flexibility” and “work-life balance”, it’s easy to forget that some desires are shaped by very practical factors. The money and time spent on commuting is by far the most frequently cited of these factors.

Lawyers might have no problem at all with their firm’s office environment; they just dislike their commute. A recent report recommended that "pre-tax season ticket loans, cycle-to-work schemes, free EV charging points, shuttle buses and localised work hubs” could tackle the cost of getting to the office, while “making anchor day office hours flexible, helping employees avoid rush hours and peak fares” could make commutes quicker and more comfortable.

2. Visibility matters

BigHand data suggests 59% of firms have no or partial data on associate skills, while 56% lack information about associate capacity. Even when firms do have this data, work is often assigned to the most proximate associate, rather than the optimal one. Lawyers who spend more time working from home are therefore likely to receive less interesting work, and fewer opportunities, than their office-going peers.

Why does this system maintain the hybrid working gap? Because for those who it disadvantages, it’s a driver of disengagement. Worker engagement is strongly correlated with the work they’re given; for instance, when Clifford Chance established a system to distribute work more fairly, their associates reported feeling far more engaged. Crucially, engaged lawyers tend to go the extra mile – literally, in the case of their increased willingness to commute to the office.

So to close the hybrid working gap we need to re-engage lawyers, and to re-engage lawyers we need to make sure they’re receiving the sort of work that makes them more likely to want to go to the office. Exciting, stimulating work that requires more in-person meetings and collaboration than work deemed less interesting. And to facilitate that even, equitable distribution of work, firms need visibility of every fee-earner at their firm – including their skills and availability – regardless of where they’re working.

Some 96% of support managers agree that better visibility of workloads would improve hybrid working. At Capacity, we’ve built a solution that provides that visibility, so that work allocators can access the best-possible resource for their tasks, and associates get a fair opportunity to complete the kind of work that’ll drive them back to the office.

3. What does flexibility mean, anyway?

When hybrid working surveys ask lawyers what they like about working from home, the word “flexibility” crops up time and again. This is often understood to mean where lawyers work, because the crux of the hybrid working debate is a question of location: working either remotely or in the office.

The missing factor in this analysis is when lawyers work. We’ve already touched on childcare responsibilities, but we can imagine any number of scenarios in which flexi-time is what lawyers are really after, not flexible working environments. Maybe an associate has a 5-a-side game, or a dinner date, and wants to work extra hours to keep that evening free. Do they care whether they do that work in the office, or is their primary motivation a matter of scheduling?

It’s possible that lawyers see working from home as an imperfect substitute for what they really want: a flexible schedule. If that’s the case, and some lawyers choose to work from home on the days they have evening plans, firms could narrow the hybrid working gap simply by reframing their policies around time rather than location. Firms may not be able to offer cast-iron guarantees on when associates can clock off, but they could explore ways in which to cater towards associate desires so that they have less cause to avoid the office.

Gradual change

We want to see firms and their people align on the vexed issue of hybrid work. Closing the hybrid working gap would make for happier, more productive, and more engaged lawyers – and that, of course, would result in more inclusive and profitable firms.

In the wake of abrupt and extraordinary changes to our working habits, we know it’s going to take time for firms to find their way to a hybrid policy that works for them. We know too that all firms are different, and some will see more merits in office work while others will see the sudden imposition of remote work as an opportunity to do things differently.

Whatever your firm’s hybrid strategy, the visibility granted by Capacity means that no work allocator is left without the information they need to match their work with precisely the right associate. And that in turn means that no lawyer is left behind, regardless of where they might be working.

WRITTEN BY

William Dougherty

Co-founder